The spread offence isn’t exactly new concept in football.

It has been around in one form or another for decades, yet today it feels everywhere. High school teams use it, college dynasties thrive on it, and even the pros have adapted to it. The term itself gets tossed around on TV broadcasts and coaching clinics.

So, what’s the big deal? And guess what? It’s not just a flashy trend – the spread offence has fundamentally changed how the game is played.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down everything about the spread offence. You’ll learn what it is, where it came from, and how it works at different levels of football. We’ll look at popular variations (from pass-happy attacks to run-first schemes), real team examples, and the pros and cons that coaches weigh.

By the end, you’ll see why this modern offensive approach has become so dominant – and what it means for football in 2025 and beyond.

What is the Spread Offence?

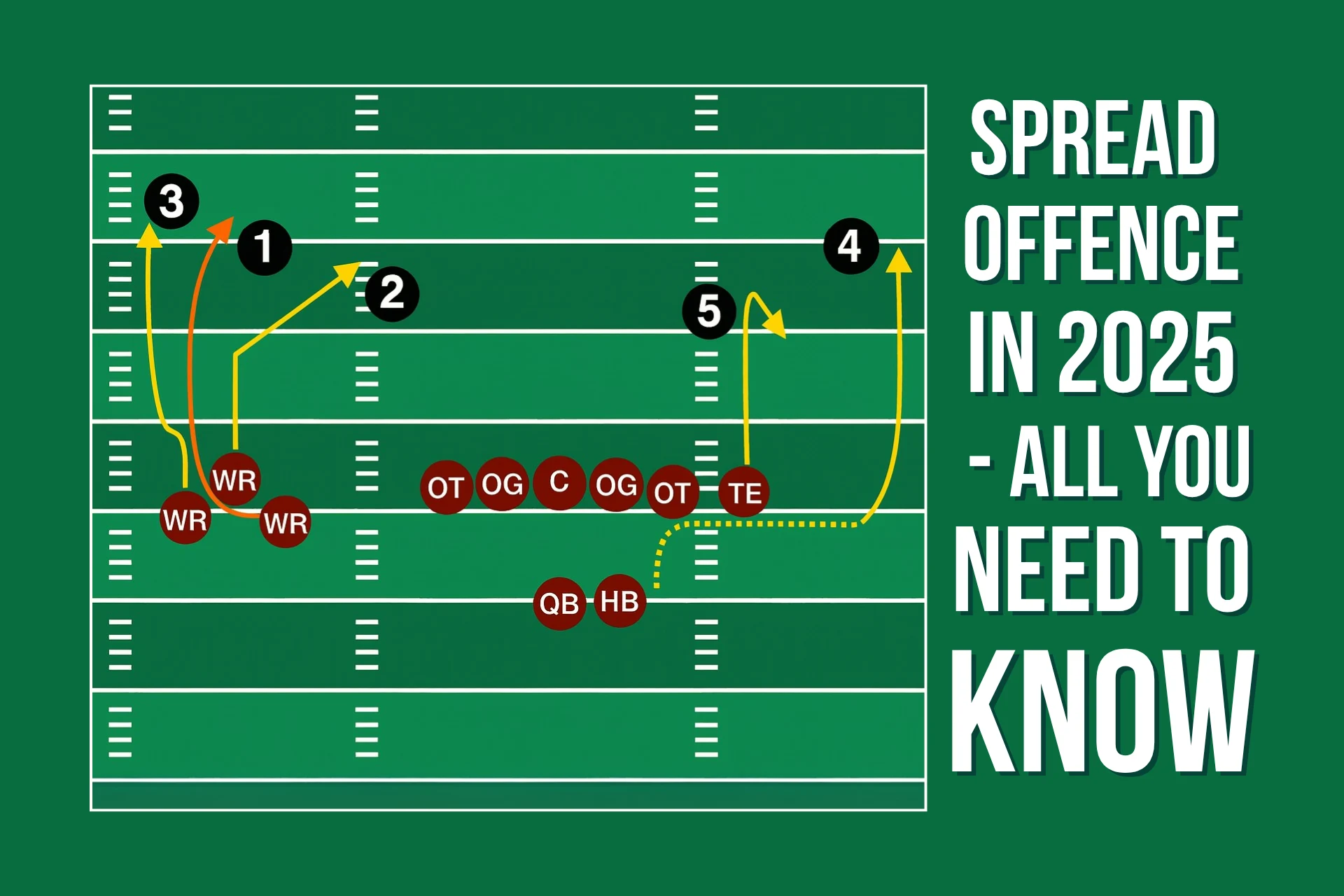

The spread offence is an offensive scheme in American (and Canadian) football built around spacing and speed. The goal is simple: make the defense defend the entire field. To do that, a spread offence lines up multiple wide receivers on each play, often 3, 4, or even 5, spreading the defense horizontally. Usually the quarterback stands in shotgun (a few yards behind the center) with one running back next to him. This wide-open formation forces defenders to cover players sideline-to-sideline, creating natural gaps (or “seams”) in the defense for big plays.

Here’s why it matters: by scattering offensive players far apart, a spread offence stretches the defense thin. A defender can no longer camp near the line of scrimmage without leaving a receiver uncovered. This spacing helps both the running game and the passing game:

-

For runs, fewer defenders are left in the tackle box (the area near the line), so there are less people to block when handing the ball off. A fast running back can find open lanes because the defense is so spread out.

-

For passes, the quarterback gets more defined reads. With defenders isolated “on an island” against receivers, it’s easier to spot mismatches and open targets. In many spread offences, quarterbacks are trained to make quick throws (like bubble screens or slants) to exploit any cushion the defense give.

Another hallmark of spread offences is tempo. Many teams that run a spread go no-huddle and use an up-tempo pace. Instead of huddling up between plays, they call plays with signals from the sideline and snap the ball quickly. Why do that? Because a fast pace prevents the defense from substituting or catching its breath. Defenders end up stuck on the field, often out of position or too tired to get fancy with blitzes and coverages. The result? The offence keeps the upper hand, and defenses are forced to simplify.

But it’s important to note that “spread offence” can mean different things to different coaches. It’s a broad term – more of a philosophy than a single playbook. As one coach put it, the definition of spread has evolved so much that it varies by who you ask.

Some teams might run the spread with four wide receivers every down, while others use multiple formations but still embrace the idea of spacing the field.

However, if there’s one consensus, it’s what Montana coach Bob Stitt said: a spread offence is truly about making the defense defend the entire field. In practice, that means lots of receivers, shotgun snaps, and making the defense cover “every blade of grass”.

Now, you might be wondering: where did this strategy come from?

Origins and Evolution of the Spread Offence

To the surprise of many, the spread offence’s roots go way back – nearly a century! Football historians trace the first spread-style ideas to the 1920s. Rusty Russell, a high school coach in Texas, is often credited as the “father of the spread offense.”

In 1927, Russell took over a small Fort Worth orphanage team (dubbed the “Mighty Mites”) that was physically outmatched by bigger schools. His solution? Spread the field. Russell deployed one of the earliest forms of a spread offence, using wider formations to create space and overcome his team’s size disadvantage.

And it worked – his undersized Mighty Mites found success by using speed and positioning to beat stronger teams.

By the 1950s, the concept was slowly entering mainstream coaching circles. In 1952, TCU coach Leo “Dutch” Meyer even wrote a book titled Spread Formation Football, opening with the line, “Spread formations are not new to football.”Clearly, forward-thinking coaches had been tinkering with spreading the field for a long time.

Still, for much of the mid-20th century, football remained dominated by tight formations and run-heavy schemes (think wishbone, Power-I, etc.). The spread offence ideas were bubbling under the surface, waiting for the right innovators to unleash them.

Fast forward to the late 1950s and 1960s: a coach named Glenn “Tiger” Ellison introduced an offense known as the Run & Shoot. This scheme was a precursor to the modern spread – it featured four wide receivers and relentless passing mixed with draws and option routes.

Ellison’s original Run & Shoot was actually started as a run-first offense in 1958, but it evolved over time to emphasize passing. Then came Darrel “Mouse” Davis, a high school coach in Oregon who fell in love with Ellison’s ideas. By the early 1970s, Mouse Davis had adapted the Run & Shoot into a pure passing machine.

He spread the field with four receivers on every play and told his quarterbacks to “read the defense and let it fly.” Davis achieved stunning success – first at Hillsboro High in Oregon (winning a state title in 1973) and later at Portland State University. His quarterback at Portland State, June Jones, would go on to spread offense fame himself, and the Run & Shoot would even make its way into the pros (more on that later).

Here’s the kicker: even as these passing concepts emerged, many coaches still hesitated to fully embrace the spread offence.

Enter a little-known California high school coach named Jack Neumeier. In 1970, Neumeier was coaching at Granada Hills High School and found inspiration in these new ideas. He created a one-back spread offence – essentially removing the traditional fullback and tight formations, and instead using three or four receivers with a single running back.

Neumeier’s offense lit up scoreboards and produced a record-setting quarterback (named John Elway – yes, that John Elway – who played for another school but benefited from Neumeier’s concepts in summer leagues).

Coach Neumeier’s creation in 1970 has since been dubbed “football’s modern spread formation ground zero”. Nobody knew it at the time, but Neumeier’s high school experiment was revolutionary and would gradually percolate through higher levels.

By the 1980s, college coaches started catching on. Many wanted the high-scoring benefits of the Run & Shoot but without its drawbacks (the pure Run & Shoot required receivers and QBs to make perfect reads on every play – tough to execute consistently).

The solution was a more coach-controlled spread offence. Instead of constant on-the-fly route adjustments, coaches built in simpler reads and used the formation itself to dictate favorable matchups.

For example, Joe Tiller at Purdue in the mid-90s adopted a spread passing attack that shattered Big Ten norms (Drew Brees, anyone?).

Around the same time, Hal Mumme and his offensive coordinator Mike Leach crafted the Air Raid offense at Iowa Wesleyan, Valdosta State, and later the University of Kentucky. The Air Raid was essentially a refined spread: four-wide shotgun sets, but with a streamlined set of passing concepts executed to perfection.

As Coach Leach famously said, “we want to throw it short to people who can score.” His teams at Texas Tech in the 2000s epitomized this, routinely leading the nation in passing yards.

But the spread offence wasn’t just about passing.

On another front, coaches like Rich Rodriguez were innovating a run-based spread. Rodriguez, at Glenville State in the 90s and later West Virginia in the early 2000s, popularized the spread-option approach.

This style used the same receiver-heavy formations, but the intention was to “spread to run.” Instead of simply airing it out, spread-option teams use a dual-threat quarterback to run the ball via option plays (like the zone read play). In a zone read, the quarterback and running back execute a handoff/read where the QB watches a specific defender.

If that defender crashes toward the running back, the QB keeps the ball and runs to the space left open. If the defender stays outside, the QB hands off and lets the running back take it. This put defenders in a no-win situation, a core philosophy of the spread-option: put one defender in conflict and “hit ’em where they ain’t.”

Coaches like Rodriguez and later Urban Meyer (at Utah and Florida) proved you could have a devastating rushing attack out of spread formations. Their teams ran circles around slower defenses, posting huge rushing totals and still hitting big passes when defenses overcommitted.

By the late 2000s, the spread offence was catching fire nationwide. It was no longer the quirky scheme of a few outsiders – it was becoming the default offense for many teams.

“Entering the 2009 season, the spread offense has never been more popular in college football,” wrote ESPN in mid-2009. From coast to coast, up-tempo spread attacks were putting up video game numbers. Even traditionally conservative coaches were adapting.

Penn State’s legendary Joe Paterno, who had run pro-style offenses for 40 years, installed a spread with quarterback Daryll Clark by 2008. And Virginia Tech’s defensive coordinator Bud Foster admitted, “I don’t think it’s a fad. It’s just part of the evolution of offense.”

Indeed, it was an evolution – one that had started decades earlier with Russell, Ellison, Davis, and Neumeier, and blossomed fully into the mainstream.

Since 2010 and beyond, the spread offence (and its principles) have only grown. Today in 2025, virtually every college team uses some elements of spread.

Even teams known for power football have blended in spread concepts to keep up. The legacy of those early innovators lives on every Saturday and Sunday.

Spread Offence in College Football

College football is where the spread offence truly became king. Over the past 20 years, it has been embraced as an equalizer and an engine for explosive offense.

Why did it catch on so strongly in the college game?

Let’s break it down.

For one, college teams have a wide disparity in talent. Not every program can recruit a roster full of huge, NFL-caliber linemen. A smaller school facing a powerhouse needed a way to neutralize size and depth advantages. The spread offence turned out to be the perfect solution.

By using a wide-open attack, an underdog team could leverage speed and scheme to upset bigger opponents. As Coach Bob Stitt noted, in college the spread became popular because “people want exciting football” – fans love it, and players want to play in offenses that score a lot of points.

Recruits, especially quarterbacks and receivers, started gravitating to schools that ran spread systems because they knew they’d put up big stats and have fun doing it.

Case in point: think of the mid-2000s West Virginia Mountaineers under Rich Rodriguez. They weren’t a traditional powerhouse, yet with a spread-option offense featuring Pat White and Steve Slaton, they torched heavyweight teams and finished seasons in the top 10.

The spread offence gave them a tactical edge. Similarly, look at the Florida Gators in 2006 and 2008 – Urban Meyer’s spread (with a hefty dose of QB runs by Tim Tebow) led to national championships. Those Gator teams proved that you could win it all with a modern spread, and many other coaches copied the recipe.

By the 2010s, entire conferences became laboratories for spread innovation. The Big 12 Conference is a prime example – teams like Oklahoma, Texas Tech, Oklahoma State, and Baylor were scoring 40-50 points per game regularly.

At Oklahoma State, coach Mike Gundy deployed a pass-heavy spread with star quarterbacks and put up record numbers. Baylor, under Art Briles, ran a unique “veer and shoot” spread that used extremely wide receiver splits and a power run game combined with deep bombs – defenses were often helpless against it.

Even the traditionally smashmouth SEC saw the light: Auburn’s 2010 title team with Cam Newton used Gus Malzahn’s hurry-up spread to devastate opponents, and by 2014 even Nick Saban’s Alabama had incorporated no-huddle spread elements under offensive coordinator Lane Kiffin.

Make no mistake, the spread offence in college isn’t one-size-fits-all. Some teams lean pass, some lean run, but they all share the DNA of spreading the field. The Air Raid teams (like Texas Tech or Washington State under Mike Leach) may throw 50 times a game, using short passes as a substitute for runs.

On the other hand, spread-option teams (like a Navy or a 2010s Auburn) might run the ball 50 times, using the threat of pass to keep you guessing. There are also hybrid approaches: for instance, Ohio State under Urban Meyer evolved into a “smashmouth spread” – they spread you out, but then they run over you with power running plays and play-action deep shots.

The versatility of the spread offence is such that coaches can adapt it to whatever personnel they have.

If you’ve got a dual-threat QB, you design more read-option plays. If you have an accurate pocket passer and speedy receivers, you air it out with four-wide sets.

Another reason college coaches love the spread: it simplifies defensive looks they face. When you line up in shotgun with four wide, many college defenses have to drop extra defensive backs into the game, often going to nickel or dime packages.

They can’t use exotic blitzes as much because there’s too much space to cover. As a result, college quarterbacks in spread systems often see simpler coverages and more predictable fronts, making their job easier.

This partially explains why you’ll see a sophomore QB in a spread offence put up Heisman Trophy numbers – the scheme is putting him in a position to succeed against defenses that can’t disguise as much.

The result?

The spread offence has produced some of the most exciting Saturdays we’ve ever seen.

From Vince Young’s heroic performance in the 2006 Rose Bowl (Texas used a spread scheme to topple USC) to Joe Burrow’s video-game stats at LSU in 2019 (a pro-style spread hybrid that shattered records), it’s clear that spread concepts drive modern college football. Even traditionally run-oriented teams have added spread packages to keep up.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that in 2025, almost every college team runs a spread offence or a close cousin of it. Three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust offenses are nearly extinct at the top level of NCAA play.

However, the natural question arises: how does this translate to the professional level?

Spread Offence in the NFL (Professional Level)

For years, people said a college-style spread offence could never work in the NFL. Pro defenses were “too fast, too smart,” and NFL quarterbacks under center was the law of the land.

Well, times have changed. While the NFL hasn’t gone to pure spread offences like some college teams, it has undeniably embraced spread concepts in a big way. In fact, the modern NFL offense in 2025 often looks a lot like a college spread – shotgun snaps, 3+ receivers, and even quarterback option runs are common sights on Sundays.

It wasn’t always so. Historically, a few maverick teams tried spread principles in the NFL with mixed success. In the late 1980s and early 90s, the Houston Oilers and Detroit Lions both experimented with the Run & Shoot offense (essentially a four-wide receiver spread) featuring quarterbacks like Warren Moon.

They put up gaudy passing stats and made the playoffs, but critics pointed out their lack of a power run game and vulnerability to certain defensive tactics. These early attempts showed flashes of how a spread offence could thrive, but NFL coaches remained largely conservative.

A turning point came in the late 2000s and early 2010s. As more and more star quarterbacks emerged from college spread systems, NFL teams faced a choice: force those QBs to learn traditional pro-style from scratch, or adapt the offense to what they do best.

Many chose to adapt. Remember the 2012 season? That year, rookies Robert Griffin III (from Baylor’s spread) and Russell Wilson (from Wisconsin/NC State) took the league by storm with option plays and shotgun sets. The Washington team implemented a zone-read option package for RG3, and he led them to a division title as a rookie.

Around the same time, Cam Newton (an Auburn spread-option product) was making linebackers look silly with designed QB runs in Carolina. The success of these players was a wake-up call: spread offence concepts can work against NFL defenses, if used wisely.

Even established NFL legends benefited from spreading things out. Take Tom Brady and the 2007 New England Patriots – that team often lined up with four or five wide receivers and no huddle.

Brady proceeded to throw 50 touchdown passes that year, breaking records in a spread-style attack. Defenses simply couldn’t match up with Randy Moss, Wes Welker, and others spread across the field. Another example is the “Greatest Show on Turf” St. Louis Rams (1999-2001) – while not called a spread offence per se, they frequently used 3-4 receiver sets and stretched defenses vertically and horizontally, much like a spread.

So what changed in the NFL? Why now?

One big factor is the influence of innovative coaches willing to import college concepts. When former college coach Chip Kelly took over the Philadelphia Eagles in 2013, he installed a no-huddle spread offence almost verbatim from his Oregon playbook. In his first year, the Eagles’ offense jumped to the top of the league in yards and points. Kelly’s NFL stint had ups and downs, but it proved that an up-tempo spread could function in the pros. More subtly, coaches like Andy Reid (Kansas City Chiefs) and John Harbaugh (Baltimore Ravens) began working spread ideas into their systems. Reid, for instance, uses plenty of shotgun, run-pass option (RPO) plays, and wide formations for Patrick Mahomes. Harbaugh built an offense around Lamar Jackson that looks a lot like a college playbook – including QB draw plays and read options – and Jackson won the 2019 MVP with it.

NFL defenses have, of course, adjusted too. They aren’t as easily fooled by simple option plays as a college defense might be. Pro defenders are extremely fast and disciplined, so some college tactics had to be tweaked. For example, NFL hash marks are closer together than in college, which means you can’t exploit wide-side runs quite the same way as in college. Also, throwing windows close faster due to the speed of NFL secondaries. But overall, NFL offenses found that spreading the field created mismatches just as it did in college. A linebacker trying to cover a speedy slot receiver in space is a favorable matchup on any level. Teams began to favor 3-wide receiver sets as their base formation – something unheard of in the 1980s. By the mid-2010s, shotgun became more common than under-center snaps league-wide.

It’s telling that even the most traditional NFL coaches have adopted spread offence elements. New England under Bill Belichick shifted to almost exclusive shotgun in the mid-2010s. The Green Bay Packers with Aaron Rodgers often use spread formations, isolating Davante Adams (previously) in space to win one-on-one. The Kansas City Chiefs, recent Super Bowl champions, embody a creative pro-spread offense: they flood the field with speed (Tyreek Hill was a prime example), use motion on nearly every play, and force defenses to cover every inch of width and depth. It’s no coincidence they’ve been nearly unstoppable at times.

As of 2025, you’ll rarely hear an NFL team labeled a “spread offense” outright – they all still maintain balanced playbooks with under-center packages, multiple tight end sets, etc., when needed.

However, the influence of the spread offence is everywhere in the NFL. The league has essentially become a hybrid of pro-style and spread.

In fact, Canadian legend Doug Flutie once remarked that the NFL has turned into what the Canadian game was decades ago: “The NFL is turning into a no-huddle, up-tempo, fast-paced, throw-the-football type of game now. The CFL has been that for the past 30 years.” His point underscores just how far the spread principles have penetrated pro football.

So, let’s talk about Canada next – because up north, the spread offence isn’t just a trend, it’s practically a way of life.

Spread Offence in Canadian Football

When it comes to Canadian football (as played in the CFL and Canadian colleges), the spread offence is not a novelty at all – it’s the standard operating procedure. Canadian football differs in some key ways: the field is wider and longer, there are 12 players per side (meaning an extra receiver on offense), and only three downs to gain 10 yards.

These factors naturally encourage a more open, passing-oriented game. As a result, Canadian teams have been using spread concepts for a very long time, well before they were cool in the U.S.

Picture a typical CFL formation: the offense might line up with five wide receivers and one running back, shotgun snap, and receivers allowed to run toward the line before the snap (the famous CFL waggle motion). That’s essentially a spread offence every down.

Canadian offenses learned that to maximize the big field, you want speed and spacing. Legends of the CFL like Doug Flutie thrived in this environment – Flutie, a shorter quarterback who faced skepticism in the NFL, went to Canada and lit up the league in wide-open attacks. He describes the Canadian style in the 1990s as “no huddle, empty backfield sets, six wide receivers, throwing the ball all over the field”.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because that’s exactly what modern spread offences do. In a sense, the CFL has been a laboratory of spread offence for decades, and the NFL only later started catching up to that excitement.

One notable aspect of Canadian spread offence is the pace of play. The CFL play clock is only 20 seconds (versus 40 in American football), which means teams naturally play faster and often forego huddles.

This up-tempo approach keeps defenses on their heels, much like the no-huddle spread teams in NCAA. Additionally, the extra receiver and larger field make zone defenses harder to play – there’s just too much ground – which often forces man-to-man matchups. A well-designed spread offence in Canadian football will isolate a single defender and make him choose (or make a mistake), turning that into a big gain.

The result?

The spread offence in Canada produces high-scoring, wide-open games that are hugely entertaining. It’s not unusual to see CFL quarterbacks throw for 5,000+ yards in a season. The philosophy is ingrained at all levels – Canadian college teams and even high schools use spread principles routinely.

And in recent years, as mentioned, this style has influenced the NFL. Coaches took notice of how the CFL game utilized motion and spacing. For instance, some of the jet motion and creative shifts you see in NFL games now have a very CFL-ish flavor to them.

In summary, Canadian football has long been a spread offence haven. The rest of the football world’s shift towards spread concepts validates what Canadian coaches and players proved long ago: if you want excitement and you want to maximize your offensive potential, spreading the field is the way to go.

Now, let’s get a bit more tactical.

Not all spread offences are identical – there are a few popular play styles and variations worth mentioning, along with their tactical nuances. In the next section, we’ll explore some of the key strategies and variants of the spread offence, from the Air Raid to the spread-option and beyond.

Variations of the Spread Offence and Key Strategies

One reason the spread offence can be confusing to pin down is because it comes in many flavors. Think of “spread offence” as a family of related strategies. Teams emphasize different things depending on their coaches and personnel. Here are some of the most notable variations and concepts within the spread family:

The Air Raid (Pass-Happy Spread)

If you’ve ever watched a Texas Tech or Washington State game under coach Mike Leach, you’ve seen the Air Raid in action. This style of spread offence is all about passing – short, medium, and deep, all game long. The Air Raid typically uses 4 wide receivers on almost every play, and sometimes a fifth as a running back who catches passes. The philosophy is to simplify the play concepts, but execute them perfectly. Air Raid teams might only run a handful of core pass plays, but they rep them to death so that every receiver and the QB are on the same page. A hallmark Air Raid play is “Four Verticals,” where four receivers sprint deep and then can settle in open spaces – it stretches a defense vertically to the max.

The tactical idea here is to “pass to set up the run,” which was the opposite of traditional football wisdom. Air Raid coaches figure that if they throw accurately to playmakers in space, they’ll march down the field consistently. Runs are used sparingly just to keep defenses honest (often draw plays or occasional zone runs). One huge benefit is that Air Raid offenses can be taught relatively quickly – it’s plug-and-play. That’s why you see some smaller colleges or high schools adopt it to great effect even without blue-chip talent. On the downside, if weather or a strong pass rush disrupts the timing, an Air Raid can stall (since it doesn’t have a heavy running game to fall back on). Still, in the spread offence spectrum, the Air Raid stands at one extreme: maximum spread, maximum passing.

Spread-Option (Run-First Spread)

On the flip side, we have spread-option offenses. These are spread offences built to run the ball – often with the quarterback as a primary ball carrier. Coaches like Rich Rodriguez, Urban Meyer, and Gus Malzahn championed this style. The spread-option uses the same principles of spacing (multiple WRs, shotgun formation) but with the intent to create running lanes and leverage advantages in the run game. How do they do that? By using option plays (like the zone read, triple option from shotgun, speed option, etc.) and modern wrinkles like RPOs (Run-Pass Options).

In a typical spread-option play, the offense might leave one defender (say, a defensive end) unblocked on purpose. The quarterback reads that defender – if the DE crashes inside to tackle the running back, the QB pulls the ball and runs around the end. If the DE stays outside, the QB gives the ball to the running back to exploit the now-lighter interior. It’s the classic option football idea (make one guy “wrong” no matter what he does) but executed out of a spread formation. Because the field is spread out, once the ball-carrier gets past the first level, there are fewer defenders left to beat, often leading to big gains.

Teams like the early 2010s Oregon Ducks made this famous – remember those lightning-fast offenses with QBs like Marcus Mariota? They were spread-option: lots of inside/outside zone reads, and a blistering tempo. These offences can put up huge rushing yards and still hit you with a surprise play-action pass to a wide-open receiver. The spread-option does require a quarterback who is a running threat and can make quick decisions. It’s a bit of a “finesse” approach in that such teams might not overpower you physically at the line, but they will run you ragged with misdirection and speed. Defenses often say it’s like defending 12 men, because the QB is effectively a running back too.

The Power Spread (Smashmouth Spread)

What if you want the best of both worlds – the spacing of a spread offence, but also the physical downhill running of old-school football? That’s where the smashmouth spread comes in. Also known as the power spread, this approach tries to “spread to run you over.” These teams still line up in shotgun and 3-4 wide sets, but they incorporate a lot of power running concepts. They’ll pull guards, use H-back blockers, and basically hit the defense in the mouth once they’ve got them spread out.

A great example was Urban Meyer’s Ohio State teams in the mid-2010s. Meyer started as a spread-option guy, but at OSU he recruited beefy offensive linemen and big running backs. He evolved his scheme into a more power-based attack while still using spread formations. The result was an offense that could gash you with QB runs and inside zone, then sucker-punch you with a deep play-action pass when you tried to stack the middle. Another example is coach Art Briles’s system at Baylor (sometimes called “veer and shoot”). Baylor would use very wide receiver splits to stretch you out, then run a power run scheme inside – if you cheated out to cover the receivers, they ran up the gut; if you crowded in, they’d throw vertical routes outside. It was pick your poison.

The power spread essentially isolates and overpowers weak spots in the defense. Think of it as a blend of brute force and finesse. To work well, it helps to have a talented offensive line and a quarterback comfortable taking some hits (since QB power runs are common). When executed, the power spread can dominate possession and still generate big plays, which is why many championship teams in recent years have had a flavor of this – balancing spread passing with a strong run game.

Pro-Style Spread (Balanced Spread)

Finally, there’s what some call the pro-style spread – basically, a balanced offensive approach that uses a lot of spread formations. NFL teams often fall in this category. They don’t abandon having a tight end or fullback at times, but they’ll frequently line up in 3-wide (11 personnel) shotgun and use college-like concepts. The idea is to combine the meticulous West Coast offense-style passing or other pro schemes with spread spacing to make it easier. As one analysis noted, RPO plays (run-pass options) are like “WD-40 for a simple zone running game” – it just makes everything smoother by adding options.

Pro-style spreads aim to be multiple yet streamlined. A team might huddle and use complex motion one play, then go no-huddle spread the next. The key is they want to maintain a balance of run and pass, similar to traditional offenses, but they recognize the value of shotgun spacing and tempo. Good pro-spread teams will do a few things really well (like inside zone run and quick slants off RPO, for example) and base their identity around that. Poor ones might lack identity by trying to copy a little of everything.

In college, you see this with teams that call themselves “multiple” – they might use a tight end and run power, then spread out four wide and run Air Raid concepts. Done right, it’s extremely hard to defend because you’re basically running a no-huddle version of a full NFL playbook. But it’s hard to pull off unless you have smart, versatile players. Still, the trend is that even very traditional programs (think Alabama, or pro teams like the Patriots) have married pro-style with spread. The lines have blurred to the point that calling something a “spread offence” might just mean “modern offense” today.

The bottom line is: The spread offence isn’t a single formation or play – it’s a collection of ideas about using space and pace.

Whether it’s a pure passing Air Raid or a run-heavy spread-option, all these variations share the core principle of forcing defenses to cover more ground and make tough choices. Coaches will continue to invent new wrinkles (like the recent surge of RPO plays, which are a spread concept that’s now even in the NFL), but they’re all part of the spread’s evolution.

Now that we’ve covered what the spread offence is, its history, use at different levels, and variations, it’s time to weigh its impact. Every strategy has strengths and weaknesses. Let’s summarize some clear pros and cons of the spread offence.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Spread Offence

Before jumping into a spread scheme, coaches always consider what they’re gaining and what they might be giving up. Here’s a look at the major pros and cons of the spread offence in football:

Advantages of the Spread Offence

Spreading the field offers many benefits for an offense. A spread offence, when executed well, can be a nightmare for defenses. Here are some of its key advantages:

-

Stresses the Defense Across the Field: By aligning multiple wide receivers, a spread offence forces defenders to cover in space and “on an island.” This means linebackers and safeties have to make tackles in open field, which often leads to missed tackles or favorable one-on-one matchups. Simply put, the defense has to defend every inch, sideline to sideline, which is tough to do consistently.

-

Fewer Defenders in the Box: With the defense spread out, there are typically fewer defenders near the line of scrimmage. This makes running the ball easier. Running backs face lighter boxes (fewer than 7 defenders), so even a modest offensive line can create creases. As one coach quipped, “you spread them out, you have less guys to block when you run the football.” In short-yardage, a spread formation can actually make it simpler to run because the defense can’t crowd everyone inside without risking a quick outside throw.

-

Enhanced Mismatch Opportunities: Offenses can deliberately line up their best athletes to attack a defense’s weakest cover players. For example, a speedy slot receiver matched on a slow linebacker is a win every time. A spread offence allows you to move players around and find mismatches easily. Many teams will use formation adjustments to get that ideal pairing – and once they see it, they exploit it.

-

Quarterback Vision and Safety: The quarterback, standing 4-5 yards back in shotgun, has a great field of vision pre-snap and is also physically farther from the pass rush at the snap. This little bit of extra space can help QBs see blitzes coming and avoid the “immediate” pressure that under-center QBs face. Defenders like defensive ends have a longer path to the QB if the offensive line uses wide splits, buying the QB more time to throw.

-

Tempo and Fatigue Factor: Most spread offences pair the formation with a no-huddle, up-tempo approach. The advantage here is two-fold: defenses can’t substitute freely, and they eventually get gassed. An exhausted defense is prone to mistakes. Offenses can run many plays quickly, and as the game wears on, those defensive linemen have their hands on hips. Fast pace also tends to simplify what the defense can do – they don’t have time to call complex schemes or adjust, leading to simpler reads for the quarterback.

-

Easy Check-Downs and RPOs: Spread offences often incorporate run-pass option plays (RPOs) and quick screens. These are easier to execute when you’re already in shotgun with wide alignments. A quarterback can quickly decide to throw a bubble screen if a defender cheats against the run. This keeps defenders honest and often turns what looks like a run into a high-percentage pass if the defense is out of position. It’s built-in insurance that works beautifully in spread spacing.

-

Maximizing Practice Reps and Inclusion: Because spread playbooks can be streamlined and teams often practice up-tempo, players get tons of reps in practice. More snaps in practice means better execution in games. Also, a spread offence can make use of many skill players – four or five receivers might catch passes in a single game, which keeps more players involved and buys team buy-in. Everyone feels like a part of the action.

-

Points, Points, Points: At the end of the day, the spread offence is known for scoring. By creating big plays and exploiting any defensive lapse (because one missed assignment can lead to a touchdown in a spread), teams tend to put up more points. Fans love it, players love it. As one high school coach said, “if you have the personnel, who doesn’t like the spread?”. It’s an exciting brand of football that can turn a single broken coverage into a quick six points.

Disadvantages of the Spread Offence

Despite all those advantages, the spread offence isn’t a magic solution. It comes with some drawbacks and risks that teams must manage:

-

Quarterback Dependency: A spread offence often puts a heavy load on the quarterback to make reads and throws on nearly every play. If your QB has an off day, the whole offense can sputter. Unlike a power-I where you might hand off 40 times, in a spread the ball is in the QB’s hands as a decision-maker constantly. A few misreads or errant throws can stall drive after drive.

-

Struggles in Bad Weather: Spread teams that rely on timing passes can struggle in rain, wind, or snow. A wet ball can neutralize a passing attack quickly. Likewise, footing can be an issue for the precise cuts receivers make. Teams that can’t fall back on a power run game might falter when Mother Nature doesn’t cooperate.

-

Quick Turnarounds for Defense: The tempo that can be an advantage can also backfire. If a spread offence goes three-and-out quickly, they might have burned less than a minute off the clock, sending their own defense right back onto the field. Do that a few times in a row, and your defense will be gassed and vulnerable. So, if the offence isn’t executing, the fast pace becomes a liability.

-

Turnover Risks: There’s an old saying: “three things can happen when you throw the ball, and two of them are bad.” In a spread, you throw a lot. Incompletions stop the clock (which can be bad if you’re trying to protect a lead late), and interceptions can be very costly. A heavy passing team runs the risk of turnovers more than a ground-and-pound team, simply by the nature of how often they sling it.

-

Short Yardage and Goal-line Challenges: When you need one or two yards, spread formations can be problematic. Without extra tight ends or fullbacks, a spread offence might struggle to get a push in power situations. Many spread teams have to get creative in short yardage – like using a quarterback draw, or quickly substituting bigger personnel which tips their hand. If they stay in spread and don’t execute perfectly, they might get stuffed on key third-and-1 or fourth-and-goal plays, where a traditional heavy set might bully through.

-

O-line and Snap Execution: Gun snaps and wider splits put certain demands on the offensive line. If your center has trouble with the shotgun snap, the whole play is blown up from the start. Moreover, linemen in a spread have to be athletic (to handle pass blocking in space and pulling on runs). If a team’s O-line isn’t up to it, a spread offence can collapse – pressure comes quick or run plays don’t develop. There’s also less margin for error in communication, since you’re often not huddling (so everyone must catch signals correctly).

-

Defensive Adjustments (Blitz & Man Coverage): A smart defensive coordinator with talent can counter a spread by doing two things: playing tight man-to-man coverage on receivers and sending blitzers to disrupt the QB. If a defense has athletes who can cover your receivers one-on-one, they can bring extra rushers on the blitz and cause chaos. The spread offence can be “in trouble” if the defense doesn’t have to respect your receivers (for example, if their corners are locking down your wideouts, they’ll blitz safeties and linebackers freely). A spread team must have answers for heavy pressure – screen passes, max protect schemes – or they risk the QB getting overwhelmed.

-

Needs the Right Quarterback: Not every QB can run a spread effectively. You generally need a quick thinker who can read defenses on the fly and either deliver an accurate pass or make the correct option run read. If a quarterback can’t make proper checks and handle pressure, the spread will expose that. In a conventional offense, a QB might be able to be a “game manager,” but in many spread systems the QB has to be a playmaker. That raises your recruiting (or personnel) requirements.

-

Less Emphasis on Power Football: Some critics of the spread say it can make a team “soft” against very physical opponents. Because you often play without a fullback or even a tight end, the inside run game is limited. Against a tough defensive front, a spread might have trouble controlling the line of scrimmage. It’s worth noting that some spread teams address this by recruiting larger linemen or by incorporating a power running package (as we discussed in the power spread segment). But if they don’t, they could be at a disadvantage in cold late-season games or against teams that excel in the trenches.

In summary, the spread offence provides a high-reward, high-risk proposition. It can yield explosive results and make a good team great, but on a bad day its flaws can be glaring. This is why some coaches tailor their spread to try to cover these weaknesses (for example, mixing in a tight end for short yardage, or slowing down tempo when their defense needs rest). Football is a game of adjustments, after all.

So where does that leave us?

The spread offence has proven its worth, but it’s not an automatic win button. It requires teaching, the right personnel, and in-game management to use its advantages while mitigating its downsides. As of 2025, the consensus is that the spread offence (and its variants) are here to stay, but defenses are continuously evolving to meet the challenge. Some believe we might see a swing of the pendulum – if every offense is spread, defenses might recruit lighter, faster players, which could open the door for a return of power running by contrarian coaches. In fact, one coach predicted that eventually defenses will slow the spread and we’ll see a bit of return to “old-school” football. We’re already seeing tiny signs of this in certain programs emphasizing fullbacks and tight ends again to exploit lighter defenses. Football strategy is cyclical, but the spread offence is now deeply woven into the fabric of the game and will influence whatever comes next.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Spread Offence

Q: Why is it called the “spread” offence?

A: It’s called the spread offence because it literally spreads the defense out. The offense lines up with wide receiver placements that stretch the defense horizontally across the field. By using 3, 4, or 5 receivers, the formation forces defenders to cover more ground and not bunch up. This “spreading” creates wider passing lanes and running lanes, hence the name. Essentially, the offence is trying to spread the defense thin and take advantage of the space that creates.

Q: Who invented the spread offence?

A: There wasn’t a single “eureka” inventor, but a few coaches are credited with pioneering spread concepts. Rusty Russell in the 1920s first used a precursor to the spread at a small Texas high school, earning him the title of “father of the spread offense”. Later, coaches like Glenn “Tiger” Ellison (1950s Run & Shoot offense) and Mouse Davis (1960s-70s, expanded the Run & Shoot) were crucial in evolving the idea of wide-open offense. In terms of the modern one-back spread offence, high school coach Jack Neumeier in 1970 developed a spread passing attack that heavily influenced today’s game. The spread offence, as we know it, is a result of all these contributions over time rather than one single inventor.

Q: Why is the spread offence so popular in college football?

A: College football embraced the spread offence because it levels the playing field and produces big points. Colleges have varied talent; not every team can recruit massive linemen or five-star athletes at every position. The spread allows smaller programs to compete by using speed and scheme instead of brute force. It’s an equalizer – a well-coached spread offence can upset a more talented traditional team by exploiting space and mismatches. Plus, it’s exciting and attracts recruits. Mobile quarterbacks and fast receivers want to play in systems where they can shine, and the spread offers that. The result has been a wave of high-scoring games and innovative offenses across college football, making the spread nearly ubiquitous at the NCAA level in 2025.

Q: Do NFL teams use the spread offence?

A: Absolutely, though they might not label it “spread.” Modern NFL offenses incorporate many spread offence elements: shotgun formations, three or more receivers, and even QB option plays. While pure college-style spread offenses (like running no-huddle every play with a running QB) are rare in the NFL, every NFL team uses shotgun and wide sets extensively now. For instance, the Kansas City Chiefs often spread defenses out to create favorable one-on-ones for their speedy playmakers, and the Buffalo Bills have run sets with four wide receivers to maximize Josh Allen’s passing options. The NFL has learned that spacing the field can help isolate matchups, which is a very “pro” concept (get your best vs. their worst). So in a sense, the NFL has blended the spread with traditional pro offenses to create a more open, high-scoring game. The days of every play being two backs and a cloud of dust are gone.

Q: How do defenses counter the spread offence?

A: Defenses have been adapting in several ways. One common adjustment is using extra defensive backs – for example, the 4-2-5 or 3-3-5 defenses (4 linemen, 2 linebackers, 5 DBs, etc.) as a base package. These schemes put more speed on the field to cover all those receivers. Defenses also emphasize disguising coverages and bringing zone blitzes to confuse the quarterback, since spread QBs often make quick reads. Another tactic is to play tight man-to-man coverage and send blitzers (essentially dare the offense to win one-on-one outside while overwhelming the QB with pressure). We’ve seen elite defenses (with very good cornerbacks) slow down spread teams by doing this – if their corners can lock down receivers, it frees up other defenders to attack the backfield. Additionally, some teams try to dictate the pace by substituting slowly or faking injuries (controversially) to slow down no-huddle teams. In summary, the defensive answer to spread offences has been to go faster and smarter: more DBs, hybrid players (linebacker-safety types), and creative pressures.

Q: Is a running quarterback required to run a spread offence?

A: Not necessarily – it depends on the type of spread. For a pass-heavy spread (like the Air Raid), a running QB is not required; you could have a pure pocket passer who distributes the ball to receivers. Examples include quarterbacks like Colt McCoy at Texas or Mason Rudolph at Oklahoma State – they weren’t known for running, but thrived in spread passing attacks. However, for a spread-option style offence, a mobile quarterback is a huge asset (almost a requirement) because the threat of the QB keeping the ball is what stresses the defense. Offenses like the one Urban Meyer ran with Tim Tebow or Chip Kelly ran at Oregon needed the QB to be a running threat to hit their peak effectiveness. Many teams find a balance: even a “pocket” QB in a spread might run the occasional zone read just to keep defenses guessing. In 2025, most spread QBs have at least some mobility, but the scheme can be adjusted. The beauty of the spread offence is its flexibility – you tailor it to your QB. If he’s a runner, you incorporate more designed QB runs; if not, you lean on quick passes and RPOs as your extension of the run game.

Q: What are some famous teams known for the spread offence?

A: There are many, but a few stand out. In college, Urban Meyer’s Florida Gators (2005-2010) and Ohio State Buckeyes (2012-2018) were hugely successful spread teams, winning national titles. Chip Kelly’s Oregon Ducks (2009-2012) were renowned for their warp-speed spread offence that piled up points. Mike Leach’s Texas Tech Red Raiders in the 2000s and later Washington State Cougars showcased the Air Raid spread, leading the nation in passing. Clemson University under Dabo Swinney (with quarterbacks like Deshaun Watson and Trevor Lawrence) ran a spread that won two national championships. In the NFL, while no team is exclusively “spread,” the 2013 Denver Broncos with Peyton Manning used a lot of spread concepts to set a then-record for points scored, and the Kansas City Chiefs of recent years (with Patrick Mahomes) use spread formations and motions as a core part of their offense. Even historically, the 1999 St. Louis Rams (“Greatest Show on Turf”) and the 2007 New England Patriots could be considered early adopters of spread principles in the NFL. These teams showed how effective the philosophy can be at every level of play.

Q: What is the future of the spread offence?

A: The spread offence has become so ingrained that it’s basically the modern game’s baseline. Going forward, we’re likely to see it continue to evolve rather than be replaced. Defenses will keep adjusting – recruiting faster, versatile players – and offences will counter with new wrinkles (for example, even more use of pre-snap motion, or innovative uses of eligible receivers like throwing to running backs and tight ends split out wide). One interesting trend is the melding of spread concepts with old-school power football (as we discussed with the power spread). We might see a cycle where, because every defense is geared to stop the spread, a few teams zig when others zag and incorporate more power formations to exploit lighter defenses. But even those teams will still use spread concepts in some situations. Essentially, the line between “spread” and “non-spread” will keep blurring. Another aspect of the future is technology and play-calling – no-huddle offenses now use sideline boards and hand signals, but we might eventually have electronic communication at the college level like the NFL, which could make tempo even faster. All in all, expect the spread offence to remain a dominant philosophy. As one coach said, it’s “here to stay” – but coaches will always be tweaking it to stay one step ahead of defenses.