The history of American football formations, it’s a wild journey through time. Early games looked nothing like the organized sport we watch today. In fact, the very first college football game in 1869 was basically a soccer-style scrum with 25 players a side. Back then, you couldn’t even pick up the ball to run – it was more like a chaotic brawl than a tactical contest.

So how did we get from that mayhem to the sleek offenses and defenses of today?

Buckle up: the evolution of American football formations is full of surprises, innovations, and a few dangerous detours along the way.

From Rugby Roots to the First Formations (1800s)

American football began as an offshoot of rugby and soccer-style “mob” football. In those early days, strategy was nearly nonexistent – it was just masses of men pushing and kicking.

Here’s the thing: by the 1870s and 1880s, pioneers like Walter Camp started adding structure to this chaos.

Guess what?

New rules introduced 11 players per side, the line of scrimmage, and a system of downs to keep possession. These changes in the 1880s turned brawls into something recognizable as football. The result? Teams began to actually huddle and align in formations instead of one big mob.

But early formations were brutal by design. Coaches realized power in numbers, and they packed players tightly to smash through the opposition. One notorious example was the “Flying Wedge” – a V-shaped human battering ram. In the early 1890s, teams like Harvard would sprint downfield from a huddled V formation, wreaking havoc. It was so dangerous that defenders literally risked life and limb trying to stop it.

Believe it or not, formations like the Princeton V and the Flying Wedge became wildly popular despite the carnage. Every play was a high-speed collision. By 1894 the injuries were so severe that officials finally banned mass-momentum plays like the wedge. This was a key moment in college football history – the first time safety concerns forced a change in formations.

But not so fast: even after the wedge was outlawed, early football remained ridiculously rough.

Coaches kept devising other power formations (the “shoving wedge,” the “turtleback”, etc.) to gain an edge. Offenses would link arms, huddle tight, and charge as a unit. It was effective, but it wasn’t sustainable. The nearly lethal nature of these formations pushed the sport to a crisis.

You might be wondering: did football almost get banned?

Yes! Around 1905, there were so many deaths that President Roosevelt demanded changes to make the game safer. Football was at a crossroads – evolve or die.

The Birth of Modern Offense: Snap, Forward Pass & Single Wing

To save football, radical rule changes arrived in 1906. Their biggest change was to make the forward pass legal. For the first time, teams could actually throw the ball downfield instead of only running or punting.

This transformed the game, but it didn’t happen overnight. Many coaches scoffed at passing initially, calling it a “sissy” play. Early passing was risky – an incomplete pass in 1906 was a turnover and a 15-yard penalty!

Still, the mere threat of a pass forced defenses to spread out. The door was opened for new formations to take advantage of open space.

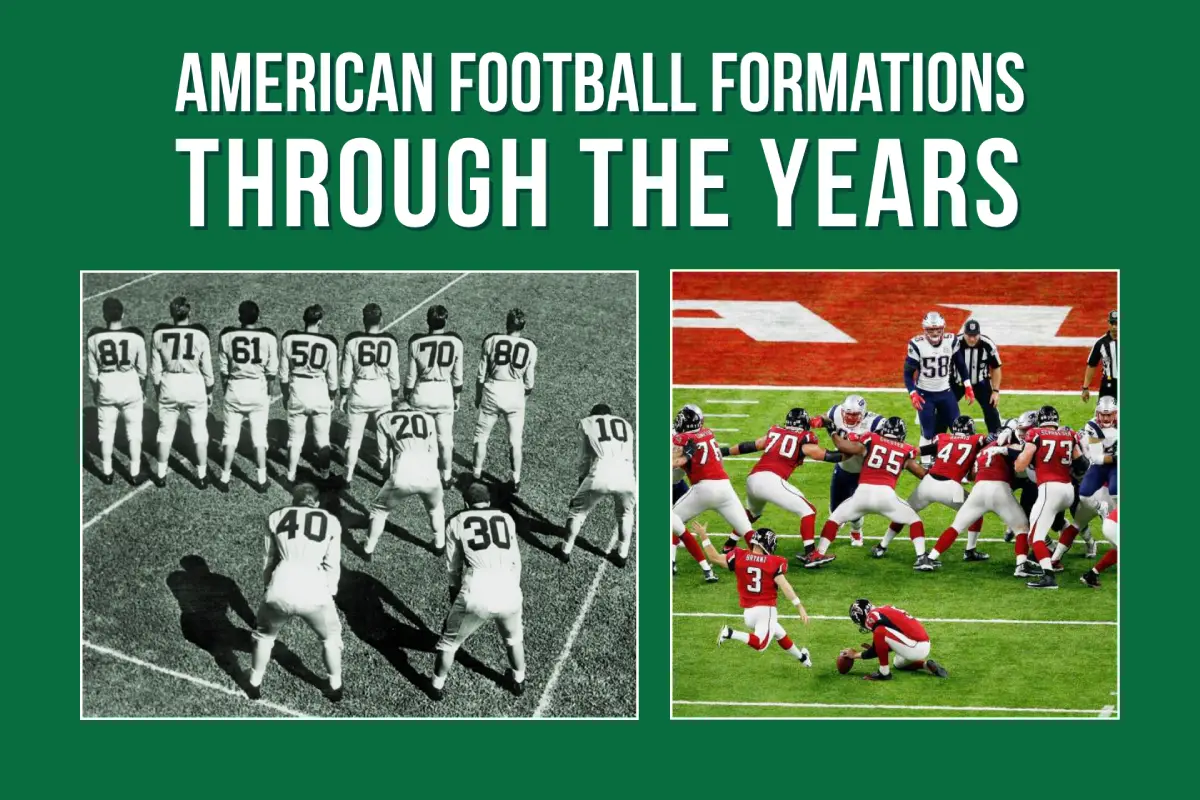

An early 1940s team lining up in the classic Single-Wing formation. In this precursor to modern shotgun offenses, the center could snap directly to one of several backs, enabling deceptive runs and passes. The unbalanced line (more linemen on one side) was a hallmark of the single wing’s power and trickery.

Enter Glenn “Pop” Warner, one of football’s first great innovators. In 1907, at the Carlisle Indian School, Warner unveiled a groundbreaking offensive formation known as the Single Wing. And guess what: the single-wing formation wasn’t about brute force alone – it was about deception. Warner’s single wing placed one lineman off-balance (unbalanced line) and had four backs in a sort of lopsided shotgun setup.

The center could snap the ball directly to a tailback or fullback instead of a quarterback under center. This gave the backfield a head start and the freedom to run, pitch, or even throw the ball.

In short, the single wing made defenses guess and gamble. It was one of the first formations to use misdirection and trick plays instead of pure power.

Pop Warner’s Carlisle team shocked powerhouse schools by combining the single wing with an aggressive passing attack. Imagine the defense’s confusion: the offense could run strong to the overloaded side, or suddenly have a back pull up and throw a forward pass – something defenders had never seen before!

In 1907, Carlisle even completed multiple spiraling passes against Penn, with a young Jim Thorpe starring in Warner’s backfield. The single wing was so successful it spread throughout college football. By the 1910s and 1920s, most teams were running some version of the single-wing or its close cousin, the Notre Dame Box (Knute Rockne’s variation with shifting backs). The single wing dominated playbooks for decades, proving incredibly versatile.

A good triple-threat tailback could run, pass, or punt from the formation, keeping defenses guessing on every down.

The single wing’s reign continued into the 1930s, but football evolution never stops. A big weakness of those early offenses was that they were predictably run-heavy.

Passing was used, sure, but it was still a run-first era. Defensive coaches eventually loaded the line of scrimmage with seven or even eight defenders (nicknamed the 7-2-2 defense, for instance, with seven linemen!) to smother those single-wing runs. Something had to give. By the late 1930s, forward passing was gaining credibility thanks to college stars and NFL pioneers like Sammy Baugh.

The stage was set for a new formation to take over – one that would truly balance run and pass. Enter the T formation.

The T Formation Revolution (1940s)

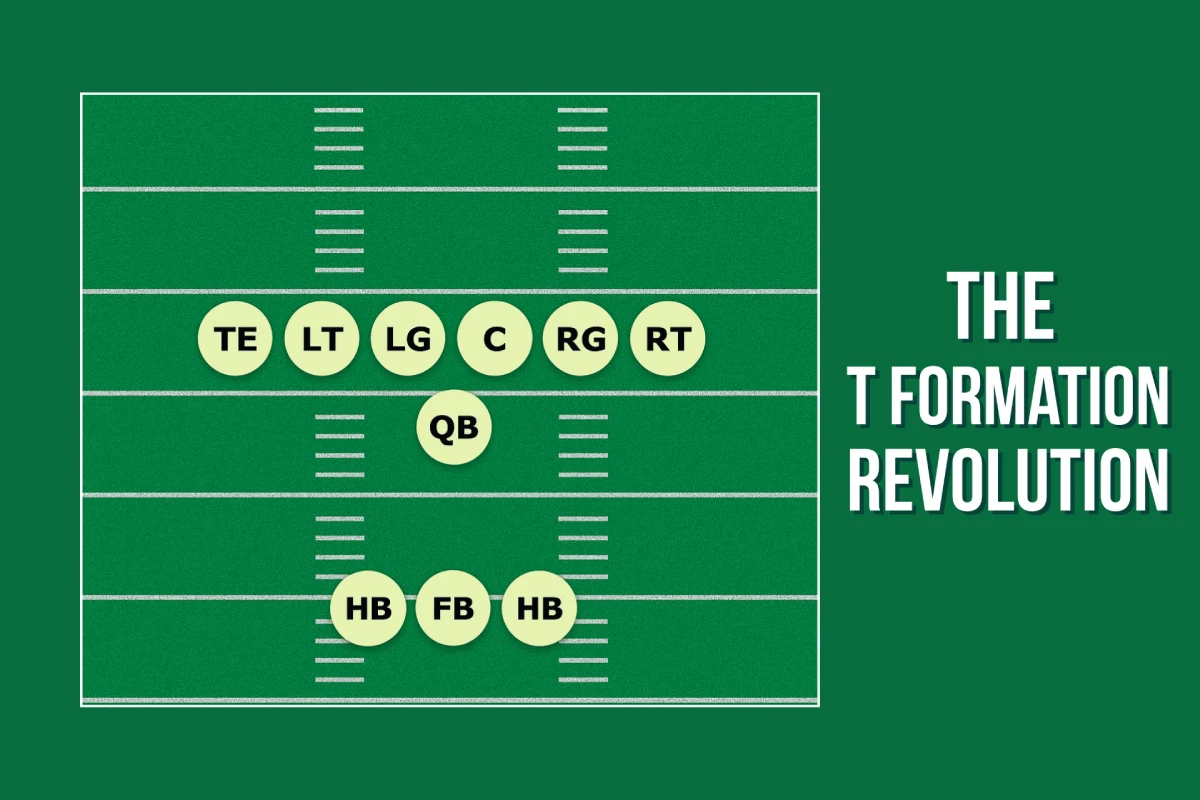

The T formation actually wasn’t new – it had been around since the 1880s – but it fell out of favor during the single-wing era. In the late 1930s, coach Clark Shaughnessy dusted off the old T formation at Stanford and brought it into the modern age.

The T formation is simple in shape: the quarterback lines up directly under center (for a hand-to-hand snap), with three backs forming a “T” behind him (usually two halfbacks and a fullback in a line). Why did this old formation make a comeback? Because Shaughnessy and others realized it could unleash a much more potent passing attack.

In the T, the quarterback is already in perfect position to take a snap and quickly drop back to throw. Plus, with two running backs flanking the fullback, the offense could fake handoffs (play-action) in ways the single wing couldn’t.

The T formation’s coming-out party was dramatic.

Here’s the kicker: in the 1940 NFL Championship, George Halas’s Chicago Bears (advised by Shaughnessy) unleashed the modern T formation on an unsuspecting Washington team and won 73-0, a massacre that stunned the football world.

Suddenly, everyone wanted the T formation. It helped that the Bears had a great T-quarterback in Sid Luckman, who could sell fakes and sling the ball downfield. The T formation eventually replaced the single wing as the dominant offensive formation. By the mid-1940s, college and pro teams alike were transitioning to the T. Even die-hard single-wing coaches gave in; for example, legendary coach Dana X. Bible retired in 1946, and his successor at Texas immediately installed a T formation offense.

Why was the T formation so revolutionary? Two words: balance and speed.

It balanced the attack (run or pass with equal ease), and plays hit faster. No more long tailback windup for a throw – the QB had the ball instantly from the center. Plus, the T allowed for new wrinkles like the man-in-motion (sending a halfback in motion pre-snap), which Shaughnessy and Halas used to confuse defenses.

Defenses, which had been geared to stop power runs, now had to cover the whole field against both runs and an aerial assault. Believe it or not, some old-timers like Coach Wallace Wade grumbled that the single wing was still superior, but they were in the minority. The proof was on the scoreboard.

By 1950, virtually every pro team and most college teams were lining up in the T formation or its variants on most plays. The era of the single wing was over; the T was king.

Of course, defensive strategy had to evolve too. The relentless running of the single wing had led many defenses to use seven-man lines. But the T formation’s passing threat forced defenses to drop more men into coverage.

A popular defense of the 1940s became the 5-3 defense (five linemen, three linebackers, three DBs), replacing the old seven-line schemes. And in the 1950s, a further innovation came along: coach Tom Landry of the New York Giants helped introduce the 4-3 defense (four linemen, three linebackers) to better counter the balanced T attacks. The chess match was fully on: formation versus formation, offense versus defense, move and countermove.

New Shapes in the ’50s and ’60s: I-Formation, Pro Set, and More

Just when you might think football formations settled into a routine, the evolution continued. By the 1950s, coaches were experimenting with how to arrange their backfields for maximum effect. Two noteworthy offensive sets emerged in this era.

First, the I-Formation. If you’ve ever watched football, you’ve seen the I – the quarterback under center, a fullback directly behind him, and a halfback (tailback) lined up deep behind the fullback, forming a vertical “I” shape. The I-formation was developed as a twist on the T formation’s backfield. Instead of two split halfbacks, one blocking fullback would lead the way for a deep tailback. This gave the running back a bit more vision and a running start.

Credit for inventing the I often goes to coach Tom Nugent, who was said to have created it at Virginia Military Institute around 1950. The idea was to replace the old single-wing concept (which Nugent felt was outdated) with a formation that still allowed power running but was simpler and more balanced.

The I didn’t catch on widely until a bit later, though. In the early ’60s, coaches like Don Coryell (yes, the future passing-game guru) and John McKay at USC embraced the I-formation. USC won a national title in 1962 heavily featuring the I – with a powerhouse tailback running behind a big fullback. Soon, everyone from Nebraska to the NFL’s Green Bay Packers had the I-formation in their playbook.

Meanwhile, another common set in the ’50s and ’60s was the Pro Set (Split Backs). Instead of an “I”, the two running backs aligned side by side, split behind the quarterback. This was basically the classic “T” backfield without the fullback directly behind. The pro set (often with two wide receivers and a tight end) became a standard NFL formation.

It was very balanced – you could run to either side or send backs out for passes. In fact, the early West Coast Offense teams under coach Bill Walsh in the late ’70s often lined up in a split-back pro set, using the backs as receivers. But let’s not jump ahead. Before the West Coast passing revolution, the ’60s had another running formation that took the college world by storm.

Cue the dramatic music: the Wishbone formation.

If the single wing was the big thing in 1910 and the T in 1940, the wishbone was the hot newness of the late 1960s. Developed by coach Emory Bellard at the University of Texas, the wishbone was a three-back, triple-option formation that literally looked like a wishbone.

The quarterback lined up under center, a fullback directly behind him, and two halfbacks positioned diagonally behind on either side – forming a shape like a Y or wishbone. The genius of the wishbone: it unleashed the triple option – the QB could hand to the fullback up the middle, pitch to a halfback outside, or keep it himself. This created an option attack that forced defenses to defend the entire width of the field.

When Texas debuted the wishbone in 1968, it was so effective that they rode it to back-to-back national championships in 1969 and 1970.

And guess what: rival coaches noticed. By the early ’70s, powerhouses like Oklahoma (under Barry Switzer) and Alabama (under Bear Bryant) copied the wishbone and built dynasties of their own.

For about a decade, the wishbone and other option formations (like the Veer and Wing-T) dominated college football, especially in the Big 8 and SEC conferences. It wasn’t pass-heavy glamour – it was ground-and-pound option football at its finest.

Why didn’t the wishbone conquer the NFL? Pro defenses were generally too fast and disciplined for pure option football to thrive, and NFL teams had success with the passing game, so they stuck to pro sets and I-forms.

But in college, the wishbone was king through the mid-1980s. It gradually waned as more schools adopted pro-style or passing offenses, but its influence persists. Believe it or not, even the modern spread-option teams owe a debt to the wishbone. As coach Mike Leach once noted, “Emory Bellard’s Wishbone is still having an impact today”, providing concepts that underpin today’s spread offenses.

The legacy of the wishbone lives on in every read-option play where a quarterback decides after the snap whether to hand off or keep – that’s essentially wishbone logic out of a shotgun!

Air it Out: The Spread Offense Revolution (1970s–2000s)

As the 1970s turned to the 1980s, football formations faced another big shift. Offenses began to open up the passing game like never before. Rule changes in the late ’70s (like liberalized blocking for pass protection and stricter rules against defensive contact on receivers) made passing more attractive in the NFL.

The West Coast Offense, pioneered by Bill Walsh’s San Francisco 49ers, proved that you could use short, precise passes as effectively as runs.

Formationally, the West Coast didn’t introduce a brand-new formation – it often used split backs or single-back sets – but it did popularize using a single running back with multiple wide receivers on the field. Coach Joe Gibbs of the early ’80s Washington team went to a single-back formation (removing the fullback for an extra tight end or H-back) to create matchup problems in the passing game.

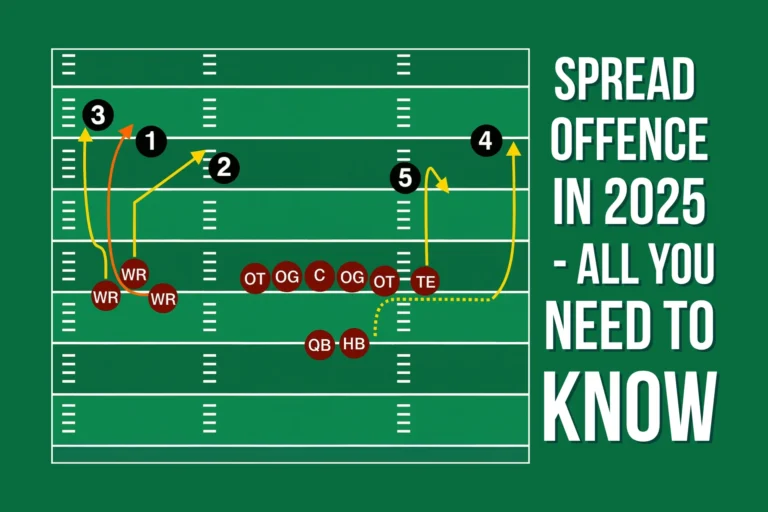

Meanwhile, college football saw innovators like LaVell Edwards at BYU, who in the ’80s routinely spread the field with four wide receivers in what was essentially an early shotgun spread attack. By the 1990s, the spread offense truly came into its own. Coaches like Steve Spurrier at Florida combined a one-back shotgun formation with four receivers to create a “fun ‘n’ gun” offense that lit up scoreboards.

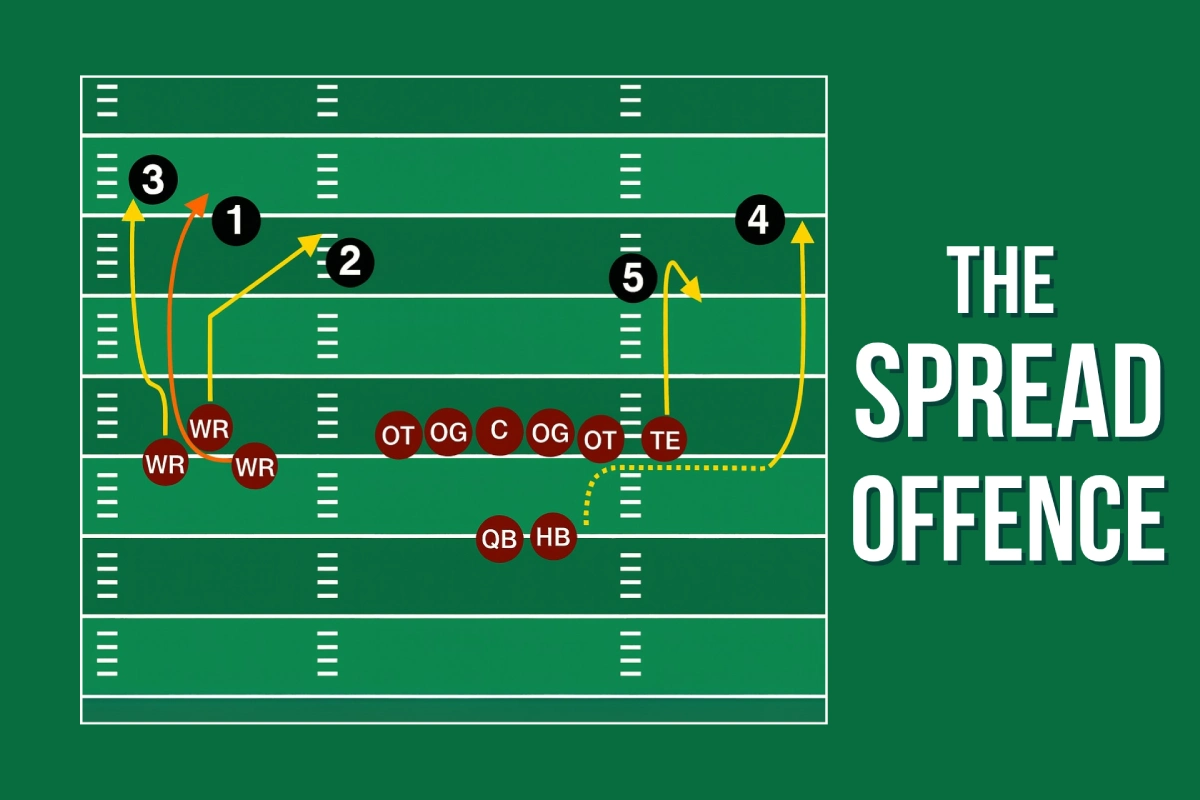

Perhaps even more influential, coach Hal Mumme and his assistant Mike Leach developed the Air Raid offense in the late ’90s, which took the spread to another level. The Air Raid often uses 10 or 11 personnel (that means one running back, zero or one tight end, and four or five wide receivers spread out) on almost every play. The quarterback stands in shotgun and the offense floods the field with receiving options. This was a sea change: no longer were “standard” formations with two backs and a tight end the norm. Now you had formations with four receivers wide as a base offense – something old-school coaches from the 1950s might have found unthinkable!

Defenses had to respond to the flood of receivers. The classic 4-3 defense (4 linemen, 3 linebackers, 4 DBs) or 3-4 defense (3 linemen, 4 linebackers, 4 DBs) started to live on a diet of substitutes. Enter the nickel defense – adding a fifth defensive back in place of a linebacker – which used to be a situational package. By the 2000s, facing 3+ receiver formations became the norm, and so did the nickel defense. In the NFL by the 2010s, teams were using five DBs on the field more than their base 4-3 or 3-4. In fact, by 2022 teams were in nickel over 65% of defensive snaps as offenses trotted out three- and four-receiver sets so often. The stats don’t lie: since 2010, offenses have lined up with three or more wide receivers on about 65% of all snaps (up from 55% a decade earlier). That’s a majority of plays with “spread” formations. Talk about a revolution!

One innovation that helped accelerate this trend was the return of an old idea: the shotgun formation. The shotgun (where the QB lines up several yards behind the center) was actually first used intermittently in the 1950s and ’60s (the San Francisco 49ers tried it in 1960). However, it became a staple formation in the 1980s and beyond. Tom Landry’s Dallas Cowboys used the shotgun on passing downs to give QB Roger Staubach more time. By the 2000s, teams like the New England Patriots were using shotgun almost every down. Fast forward to today: many offenses essentially live in the shotgun, combining it with spread sets. Some offenses even go empty backfield (five wide, no running backs) on occasion – the ultimate spread formation, which tells the defense “we’re absolutely passing.”

Another blast from the past reappeared in 2008: the Wildcat formation. This was basically the single wing reborn – a running back taking a direct snap in shotgun, with the quarterback split out as a decoy receiver. The Miami Dolphins famously used the Wildcat to stun the Patriots in 2008, and for a couple of years a Wildcat craze swept through the league. It ultimately settled down (defenses adjusted quickly), but it was a fun reminder that even 100-year-old ideas (Pop Warner would have smiled) can become new again in the right situation.

And we can’t forget the Pistol formation, developed by Coach Chris Ault at Nevada in the mid-2000s. The pistol is like a hybrid of shotgun and single back: the quarterback is about 4 yards behind center (instead of 7 in a typical shotgun), and a running back is directly behind the QB (like a shortened I-formation). The pistol allowed for effective read-option plays because the running back still has a downhill path, and the QB is in good position to run or throw. Teams with mobile quarterbacks – think early 2010s 49ers with Colin Kaepernick or the RG3-era Washington team – used pistol sets to great effect.

The bottom line? Modern offenses are an eclectic mix of old and new formations. On one play, a team might line up with five wide receivers (a concept that would amaze a 1930s coach). On the next play, that same team might line up in a Power-I with a fullback and two tight ends for a short-yardage run – straight out of 1950. Coaches now have a huge menu of formations to choose from, and they game-plan specific sets to exploit opponents. Yet, despite all the changes, the goal remains the same: find a formation that gives your team a strategic edge.

Defensive Formations Adapt and Evolve

Offenses haven’t had all the fun – defensive formations evolved in parallel to counter each offensive revolution. Let’s rewind to the early days: in the 1910s and 1920s when single-wing offenses ruled, the standard defense was a brute-force alignment like the 7-2-2 (seven linemen, two linebackers, two defensive backs) or the 6-3-2. These put many big bodies on the line to stand up to power runs. Passing wasn’t much of a concern, so secondaries were thin.

Then came the widespread passing threat in the 1940s with the T formation. Defenses responded by dropping men off the line. By the 1950s, one of the most common defenses was the 5-2-4 or 5-3-3 (often called the 5-2 Oklahoma defense in college). Soon after, Coach Tom Landry and others innovated the 4-3 defense – four down linemen, three linebackers, and four defensive backs. The 4-3 gave a solid front against the run but more agility in the linebacker level to cover short passes. It became the base defense in the NFL for decades. Many of the great defenses of the ’60s (like Vince Lombardi’s Packers or the Fearsome Foursome Rams) were built on the 4-3.

In the 1970s, a new base defense emerged: the 3-4 defense. The Pittsburgh Steelers “Steel Curtain” used a version of it, and coaches like Chuck Fairbanks and Bum Phillips popularized the 3-4 in pro football. With three linemen and four linebackers, the 3-4 was versatile and made it harder for offenses to identify where the fourth rusher was coming from. By the ’80s, roughly half the NFL teams ran a 3-4 as their base, while the other half stayed 4-3. (This remains true even into the 2020s – teams alternate between 4-3 and 3-4 preferences, and some use hybrid fronts.)

Defenses also developed special packages for passing situations. The Nickel defense (5 DBs) which first popped up in the 1960s became more regularly used on third downs. By the 1990s, the Dime defense (6 DBs) was common in obvious passing scenarios. The aggressive 46 Defense (a variation of 4-3) introduced by Buddy Ryan with the ’85 Bears showed how alignment could confuse offenses – he brought safety men up like extra linebackers and overwhelmed blocking schemes.

Today, defenses are in sub-packages (nickel, dime, etc.) more often than their base formation, due to pass-heavy offenses. As noted, teams now play nickel well over half the time. because offenses line up with three or more wide receivers so frequently. Modern defensive formations are multiple and hybrid – on one play a defense might show a 4-2-5 (4 linemen, 2 linebackers, 5 DBs), next a 3-3-5, next a 4-3, etc., all with the same personnel on the field. Players are more versatile now; a safety might drop down as a pseudo-linebacker, or a defensive end might stand up like an outside ’backer.

And guess what: all this strategic shuffling is in direct response to offensive formations. As offenses spread out, defenses have added speed and coverage. When offenses go heavy, defenses bring in beefier formations. The cat-and-mouse game continues.

A Never-Ending Evolution

From the mass formations of the 19th century to the spread formations of the 21st, American football has been in a constant state of tactical evolution. Each new formation – whether it was the single-wing, T formation, wishbone, or shotgun spread – arose to exploit some defensive weakness or take advantage of unique talent. And each time, defenses adapted with new alignments of their own. The evolution of American football formations is really the story of the sport itself: a balancing act between innovation and reaction, between offense and defense.

Today’s playbooks are like museums of formation history. Coaches can deploy a 1920s formation one play and a 2020s formation the next. It makes the sport incredibly rich and strategic. If you watch an NFL or college game now, notice the formations: one moment a team will be in a three-wide shotgun, then a classic I-formation, then a funky spread with four receivers, then a goal-line jumbo package with extra linemen. It’s all a product of 150+ years of trial and error on the gridiron.

So next time you hear an announcer talk about a team “lining up in the shotgun” or “coming out in a nickel defense,” you’ll know these terms are chapters in a much larger story. American football formations didn’t just evolve – they exploded into countless variations in a quest for the perfect play. And coaches will never stop searching. The evolution continues, and who knows what the next revolutionary formation will be? One thing’s for sure: it’ll have roots in the past and an eye on the future, just like every great innovation in the evolution of American football formations.

(Internal Link Example: Learn more about early football history and rules changes on the official American Football page. )

FAQ: Evolution of Football Formations

Q1: What was the first offensive formation in American football?

A: In the very beginning (late 1800s), there weren’t well-defined formations – teams used mass plays resembling rugby scrums. The first notable “formation” was the Flying Wedge in 1892, where players formed a V-shape and charged downfield. It was extremely dangerous and got banned by 1894 for safety reasons. After that, early formations like the single-wing (1900s) became the foundation of offense, emphasizing unbalanced lines and direct snaps to versatile backs.

Q2: Why was the single-wing formation so important?

A: The single-wing (devised by Pop Warner in 1907) was crucial because it introduced deception and flexibility to offense. It featured an unbalanced line and a shotgun-style snap to a tailback, who could run, pass, or kick. This kept defenses guessing. The single-wing dominated football for decades as it was more strategic than the brute-force formations before it. It’s essentially the great-grandfather of today’s shotgun and Wildcat formations.

Q3: When did passing formations become common?

A: Passing started to become mainstream with the T formation revival in the 1940s. The T formation put the quarterback under center, making the forward pass quicker and more practical. By the 1950s and ’60s, formations often featured two wide receivers (flanker and split end in a pro set) to stretch defenses. However, truly pass-heavy formations (three, four, five receivers) took off from the 1980s onward. The West Coast Offense used single-back and split-back sets to facilitate passing, and by the 1990s the shotgun spread with 4+ wideouts was common in college and creeping into the NFL.

Q4: How have defensive formations changed in response?

A: Defenses evolved significantly to counter offensive trends. In the early 1900s, defenses were in 7-2-2 or 6-3-2 setups to stop strong runs. As passing grew, they shifted to 5-3 and 4-3 defenses by the mid-20th century, adding more defensive backs. The 3-4 defense became popular in the 1970s for its versatility. In modern football, the sub-package is king – teams use nickel (5 DBs) or dime (6 DBs) formations most of the time to counter spread offenses. For example, against three-receiver sets, a nickel 4-2-5 defense is now a base alignment for many teams. Defensive formations keep adapting, from the 46 defense in the ’80s to today’s hybrid schemes.

Q5: What is the most common offensive formation in today’s game?

A: In the NFL and college, you’ll see a ton of 11 personnel shotgun formations – that is 1 running back, 1 tight end, and 3 wide receivers, with the QB in shotgun. This essentially gives a three-receiver spread look on most downs. It’s popular because it’s very balanced – you can run or pass effectively from it. Many teams also use variations like single-back under center for play-action, or empty backfield in obvious passing downs. But the days of two backs and two tight ends every play are gone. Now it’s about spacing the field with multiple receivers. According to recent statistics, about 65% of plays involve three or more receivers on offense, so that three-wide shotgun look is the closest thing to a “standard” formation today.